Endangered way of life

Tax hikes threaten islanders' homes

By Farah Stockman, Globe Staff, 12/8/2002

HEBEAGUE, Maine -

A year ago, annoyed that property taxes on Hope Island had more than tripled,

its sole occupants, a New York millionaire and his wife, sought to escape

taxes by seceding from their town. They argued that their remote mansion,

boat house, and helicopter pad should constitute its own town, and that therefore

they should be able to set their own tax rate. HEBEAGUE, Maine -

A year ago, annoyed that property taxes on Hope Island had more than tripled,

its sole occupants, a New York millionaire and his wife, sought to escape

taxes by seceding from their town. They argued that their remote mansion,

boat house, and helicopter pad should constitute its own town, and that therefore

they should be able to set their own tax rate.

At the time, residents of the neighboring island of Chebeague laughed

at the couple, but this summer, when land on Chebeague was revalued, doubling

taxes on fourth-generation lobstermen, they began their own efforts to avoid

taxation. Now, many of the 320 year-round residents of this centuries-old

fishing village are pushing to amend Maine's constitution to give some homeowners

the same low tax rates offered to nature preserves, wildlife sanctuaries,

farms, and woodlands.

''Island communities are completely endangered,'' said David Hill, who

authored the current plan after deciding that secession was impractical for

Chebeague. ''At the turn of the century, there were 300 island communities

in Maine. ... Now there are 14. If there were any wildlife species with that

kind of decline, they'd be protected.''

The proposal, one of at least three antitax measures that could be considered

by the Maine Legislature in the coming months, illustrates the lengths to

which Mainers are willing to go to avoid one of the nation's highest property

tax burdens. Combined with the antitax fight on Hope Island, the move highlights

one of the most pressing issues in the state, and shines a spotlight on the

changing face of Maine's coast.

Seated in the cab of his pickup truck, with salt-encrusted boots and a

shotgun, Leon Hamilton looks like what his friends call him: ''a dying breed.''

The 54-year-old used to be one of a dwindling number of lobstermen working

the island's shores. Now he drives the ferry - a job he's grateful for because

it helps him keep up with the fastest-growing living expense here: property

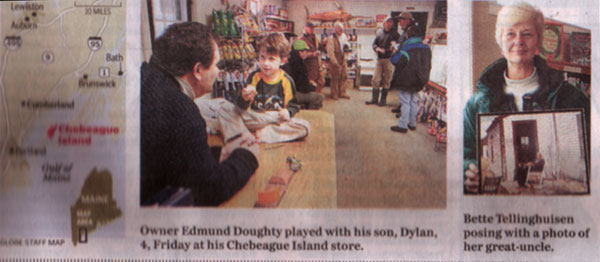

taxes. On Chebeague, an island with one taxi, one grocery store, one police

officer, and a phone book as thin as a menu, ''extinction'' is what long-time

islanders fear.

''It's just a matter of time,'' Hamilton said. ''There won't be any lobstermen;

there won't be any boats. There will just be mansions on the water.''

This summer, Hamilton's taxes increased from $4,000 to $8,000. The narrow

strip of azure sea that shows through the birches from his kitchen window

was meant to help his ancestors keep an eye on their boats. But now his ''ocean

view'' has sent his taxes skyrocketing because wealthy out-of-staters - mostly

from Massachusetts - will pay generously for any patch of blue.

Hamilton admits that, for now, he can afford the taxes, but others are faring far worse.

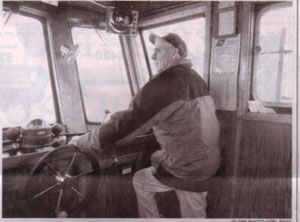

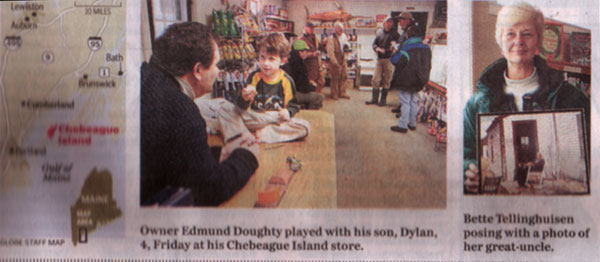

Bette Tellinghuisen, whose land has been in the family since 1880, saw

her taxes rise from $5,500 to $11,000 - half of what she earns annually at

her own financial analyst business. ''I was physically ill when I got the

bill,'' Tellinghuisen said.

Wilbert Munroe, one of about 35 lobstermen left on the island, saw taxes

on his modest house jump from $2,200 to $6,000 - a sum he says equals all

the money he earned this summer after he paid to repair his boat.

''If you can see the ocean, it costs you money,'' said the tattooed 70-year-old,

standing amid his lobster traps and next to his caved-in garage.

Pamela Johnson, a real estate broker who grew up on Chebeague, says out-of-staters

consider it a bargain to pay as much as $460,000 for a seafront house.

''I have a number of people calling from Cape Cod,'' she said. ''They are feeling crowded there.''

It doesn't matter much, islanders say, that their property values also doubled.

''My property is not for sale and won't be for sale, as far as I'm concerned,''

said David Stevens, the island's mechanic, whose house has been in his family

for 100 years. ''Property taxes are the biggest threat to our community.

If you look into the future, you can see all the property on the island bought

by people from away and the island community disappearing.''

Fearful and angry about the revaluation, Hamilton and the others rallied

this summer at near-weekly tax meetings that evolved into a group called

Save Our Island. At first, the group wanted to secede from Cumberland - just

like the wealthy couple on nearby Hope Island. But secession was deemed impractical,

and many did not support it because their inland houses actually saw taxes

fall.

So now, many are putting their faith in the plan drawn up by Hill, a Save

Our Island activist, to protect homes just like tracts of wildlife. Under

Maine's constitution, only nature conservation efforts - open space, farmland,

forests, and sanctuaries - can escape market-value property taxes. Hill's

proposal would add another eligible category: ''Land used for long-term ownership.''

Modeled on Maine's Tree Growth Tax Law, which was designed to preserve

forested land, Hill's plan would allow Maine landowners to voluntarily enter

a land bank where property taxes would stay low for as long as a home remains

in a family's hands. If the property is ever sold, owners would face taxes

and penalties so steep, Hill argues, they would make up for the revenue lost

by the lower taxes.

So far, community groups and politicians have expressed interest in exploring

the plan, and Hill hopes a coalition at Maine's State House will examine

it this month.

David Platt, director of publications at Maine's Island Institute, which

is dedicated to preserving human life on the islands, said he expects the

Legislature to enact some form of this proposal in the coming years.

''The idea of conserving human habitats sounds strange, until you consider

the alternative,'' Platt said, adding that preserving fishing communities

benefits the public just like conserving a wildlife sanctuary.

But Cumberland officials were more guarded about a proposal that they

fear could help rich out-of-staters more than lobstermen, and sap needed

revenue from the town.

''The last thing we want to see is the lobstermen leave Chebeague,'' said

Jeff Porter, chairman of the Cumberland Town Council. ''But you have to look

at it in the broader context of doing what is right for the town of Cumberland.''

On Hope Island, a sailboat's sprint from Chebeague, John and Phyllis Cacoulidis

say they want to secede from Cumberland and become a town of two because

their taxes have risen from $5,000 to $50,000 since 1993 - even though they

don't use the town's water, sewer, trash, police or school system.

''I'm looking to pay my fair taxes ... but they want to tax people to

death,'' said John Cacoulidis, 72, who paid $1.3 million for the 89-acre

island a decade ago and built a six-bedroom guest house, a 14-stall stable,

a chapel, and two artificial lakes.

Cumberland officials point out that Cacoulidis bought the island knowing

there were no services on it and that the couple's effort to become their

own municipality has little chance of success.

''There is no one in Maine that is going to submit a piece of legislation

that's going to allow Hope Island, which is owned by a New Yorker, to secede,''

said Cumberland's attorney, Kenneth M. Cole III.

But Cumberland went through the legal motions: a public hearing, mediation,

and a special election, in which Phyllis Cacoulidis, the island's only year-round

resident, was the sole person who could cast a vote. (She voted yes.) She

has threatened to pursue the matter in federal court.

The couple's efforts earned them a lot of negative publicity, with newspapers

calling them ''wrong,'' ''shortsighted,'' and ''the most annoying landowner

from faraway.''

John Cacoulidis, who is also pushing for the construction of a controversial

skyscraper in South Portland, earned additional ire from Chebeague, where

rumors abound that he chases away fishermen who float over to say hello.

In turn, Phyllis Cacoulidis accuses Chebeague residents of spying on her

with binoculars and ''laughing in our face'' about the couple's bid for secession.

But now, Cacoulidis says if his plans to secede fail, he will join the land bank program proposed by Chebeague activists.

''I am interested,'' said Cacoulidis, adding that he is like the fishermen. ''I want to keep my house in the family.''

This story ran on page B1 of the Boston Globe on 12/8/2002.

© Copyright 2002 Globe Newspaper Company.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

HEBEAGUE, Maine -

A year ago, annoyed that property taxes on Hope Island had more than tripled,

its sole occupants, a New York millionaire and his wife, sought to escape

taxes by seceding from their town. They argued that their remote mansion,

boat house, and helicopter pad should constitute its own town, and that therefore

they should be able to set their own tax rate.

HEBEAGUE, Maine -

A year ago, annoyed that property taxes on Hope Island had more than tripled,

its sole occupants, a New York millionaire and his wife, sought to escape

taxes by seceding from their town. They argued that their remote mansion,

boat house, and helicopter pad should constitute its own town, and that therefore

they should be able to set their own tax rate.